Anyone reading the food news these days would think that Big Food is dead. In recent years, analysts have been alert to the trends, publishing excellent reports such as Is Big Food In Trouble? (A.T. Kearney/The Hartman Group, 2016), Invasion of the bottle snatchers: Smaller rivals are assaulting the world’s biggest brands (The Economist, 2016) and Special Report: The War on Big Food (Fortune, 2015).

Today, journalists covering the food beat are less circumspect. Three headlines from February-March 2018 declare The death of the ‘Big Food’ era is imminent after the industry’s biggest lobbying group crumbles (Quartz), Kraft Heinz Co. Out of Ideas (Food Logistics), Big brands lose pricing power in battle for consumers (Financial Times).

There is evidence to support these declarations. Read any of the “What’s Hot” or “Top Trends” reports for 2018 and you’ll see a long list of drivers of food choice that the Big Food companies are not necessarily built to address: products that are fresh or minimally processed, sourced locally, artisanal, simple, clean and produced sustainably—from companies that are small, transparent and socially responsible. For this shift in consumer mindset and values we can thank the Good Food movement and the many food entrepreneurs who have stepped into the arena, shaking up the status quo and creating demand for products that are more handcrafted and sustainably produced.

Challenged by their business models and innovation capabilities, large consumer products companies are indeed losing market share to smaller upstarts, but Big Food is not rolling over yet. These companies are innovating within their corporate constraints and employing new strategies with a goal toward growth. We will be covering these trends and strategies in detail on our blog over the coming months. In this post I’ll lay them out in broad strokes with links to a few examples to set the stage, and invite your perspective.

5 Food and Beverage Growth Strategies

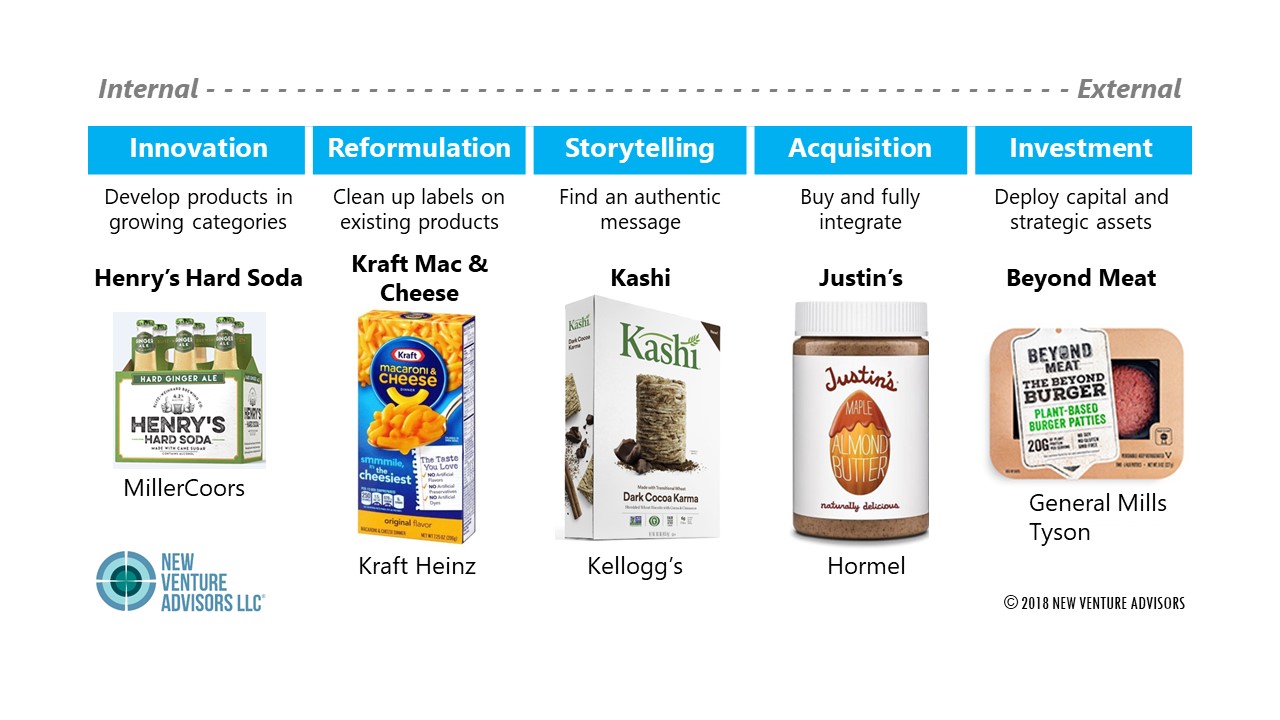

We see five main ways that large food and beverage companies are using their scale and business processes to respond to these changing consumer preferences. On a spectrum from internal to external, they include research and development (R&D) processes for product innovation and reformulation, marketing processes for branding and storytelling, financial and operations processes for acquiring and integrating fast-growing brands (also called M&A, mergers and acquisitions), and corporate venturing processes for investing in early stage businesses that are developing promising new brands. These are depicted in the graphic below with recent examples of brands that the big companies have successfully grown using one or more of these strategies.

Innovation

In-house innovation is the business process that the big companies have struggled with most in satisfying the changing tastes of consumers. This is partly due to the fact that consumer tastes are at odds with the Big Food business model, but a great innovation capability can produce new business models as well as new products. Yet, efforts to embed a dynamic innovation capability in large, risk-averse institutions are immensely challenging, despite the sophistication of their strategy and R&D teams. Raising the stakes is an expectation in many firms that any new item must achieve $100 million in sales within the first year of introduction in order to justify continued sales and marketing support, although that threshold may be changing. According to the New Product Pacesetters report from IRI Worldwide, only five new products in 2016 crossed the $100 million threshold, and 80% earned less than $40 million as consumers eschewed mass brands for niche products. These challenges have led the big companies to focus on launching new items in proven, fast-growing categories that are aligned with their current business models, commonly brands with an “artisanal-like” quality.

One such example is MillerCoors’ introduction of Henry’s Hard Soda. This category of carbonated beverages fortified with beer began to boom in the U.S. after Waukonda, Illinois-based Small Town Brewery introduced the Not Your Father’s line of flavored beer in 2010. By 2016, this small craft brewery had achieved $114 million in sales for its top-selling root beer product, an unlikely leap even for the fast-growing craft beer industry. The beverage giant was quick to respond. MillerCoors introduced Henry’s in 2016 from its Blitz-Weinhold subsidiary, promoting a craft image with a backstory about the eponymous nineteenth-century brewer Henry Weinhard. The product also promotes its use of cane sugar in response to consumer backlash against high fructose corn syrup. Henry’s achieved $50 million in sales within its first year, according to IRI.

Reformulation

The consumer’s demand for clean labels that have only a few, “natural” ingredients that are easily pronounced is a major challenge for companies that have a core competency in creating convenient, inexpensive products with long shelf-life. We probably have Michael Pollan to thank for the rush to cleaner labels. This activist, professor, journalist and best-selling author writes extensively about the American food system. As far back as 2007 in a New York Times editorial he was touting “Especially avoid food products containing ingredients that are a) unfamiliar, b) unpronounceable c) more than five in number.” Today, the term “clean” appears on almost every food trend listicle, and the big companies have responded by reformulating and cleaning up labels on their flagship brands and introducing flanker brands designed to meet these consumer preferences.

A favorite example is Kraft Macaroni & Cheese (a brand I once promoted during my time at Kraft Foods). Early in 2015 the company signaled that it would remove all artificial flavors and dyes, but waited almost four months after the switch in 2016 to announce it to the world. By that time 50 million units had sold and “essentially no one noticed” according to the company. This strategy may not reverse the tide of consumers leaving the category in favor of fresher alternatives, but it certainly avoided a reformulation disaster ala New Coke.

Storytelling

NVA has been working at the most grassroots level of the food industry since its inception after my departure from Kraft in 2008. We have supported the farmers, food access organizations, nutritionists, health care providers, community planners, environmentalists, labor rights organizations, good food product innovators, shoppers, buyers, distributors and activists representing every aspect of the food system. When a consumer chooses a product that is organic or sustainably produced, from a company they consider to be transparent and socially responsible, we understand at a systems level what this means to them. And we know, as they do, when a product claiming these attributes passes the sniff test and when it doesn’t. We have seen organizations eager to promote standard business practices in a way that positions them favorably against these trends. Frito-Lay’s 2009 Lay’s Local campaign (“Proudly Made Locally and Across America”), and more recent ads from General Mills implying its Progresso soup ingredients are sourced from local farms are just two examples of storytelling that many construe to be inauthentic because it does not reflect a change in business practices to address the issues at the heart of the Good Food movement.

By comparison, one brand marketed by a large consumer products company that has become an authentic storyteller by this measure is Kashi, owned by Kellogg’s. The company came to this point after a litigious battle over false advertising claims related to undisclosed genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in its products. Today, Kashi products are non-GMO certified, and most of the real estate on Kashi packages tells the stories of the farmers and suppliers who provide the ingredients. They have also launched a Certified Transitional Program that purchases ingredients from farms in the process of transitioning from conventional to organic practices, using its scale and market power to make a big impact on increasing sustainable land use.

By comparison, one brand marketed by a large consumer products company that has become an authentic storyteller by this measure is Kashi, owned by Kellogg’s. The company came to this point after a litigious battle over false advertising claims related to undisclosed genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in its products. Today, Kashi products are non-GMO certified, and most of the real estate on Kashi packages tells the stories of the farmers and suppliers who provide the ingredients. They have also launched a Certified Transitional Program that purchases ingredients from farms in the process of transitioning from conventional to organic practices, using its scale and market power to make a big impact on increasing sustainable land use.

Acquisition

As the strategies move toward the external end of the spectrum, we start to see the literal merging of big and small food, where consumer products companies acquire the innovation they cannot or choose not to develop in house. While this may ruin it for some diehard small food consumers, when the time comes to reap the reward of their hard work and innovation, the reality for many food entrepreneurs is that they have no better option than to exit the business by selling it to a much larger consumer products company. One of the first such deals to raise criticism was Gary Hirschberg’s sale of his Stonyfield Farm yogurt business to Groupe Danone. As Hirschberg related years later at the Good Food Conference in Chicago, he did so because he could find no other acquirer, and added as a point of pride that Danone adopted many of his company’s business practices while he remained active as chairman. In fact, this is one of the main reasons Big Food is hunting for early stage M&A deals. They not only want to acquire products that will deliver growth, they want to acquire the entrepreneurial energy and expertise in alternative business models that have made the startups successful, and are careful to not over-engineer the integration. Many of the acquired companies continue to operate as separate business units under the leadership of the entrepreneurial founder.

Another great example of this is Justin’s nut butters, a product born in the founder’s kitchen out of his frustration in finding natural, convenient sources of protein for his active outdoor, vegetarian lifestyle. As the company has grown, Justin has remained committed to sustainable practices, integrity and transparency every step of the way. Hormel purchased Justin’s for $286 million in 2016 to expand its category presence after acquiring Skippy peanut butter in 2013. The rationale for both companies was efficiency in supply chain, R&D and distribution, yet Hormel has no intention of changing Justin’s mission and values. The company continues to operate out of its Boulder, Colorado headquarters and keeps the founder’s story in the forefront of its marketing communications.

Another great example of this is Justin’s nut butters, a product born in the founder’s kitchen out of his frustration in finding natural, convenient sources of protein for his active outdoor, vegetarian lifestyle. As the company has grown, Justin has remained committed to sustainable practices, integrity and transparency every step of the way. Hormel purchased Justin’s for $286 million in 2016 to expand its category presence after acquiring Skippy peanut butter in 2013. The rationale for both companies was efficiency in supply chain, R&D and distribution, yet Hormel has no intention of changing Justin’s mission and values. The company continues to operate out of its Boulder, Colorado headquarters and keeps the founder’s story in the forefront of its marketing communications.

Investment

Perhaps the most surprising and exciting innovation in Big Food is the rapid emergence of corporate venture groups, funds, accelerators and incubators. Corporate venture groups differ from the traditional M&A model in that they provide seed and early stage financing, but do not buy the businesses outright. Similar to traditional private equity or venture capital firms, many corporate venture groups actively manage investment funds, typically deploying $100-$150 million in venture capital across a number of early stage businesses.

Many of these groups and funds provide more than financing; they offer value-added business assistance and relationships to benefit the companies in their investment portfolios. Corporate accelerators and incubators primarily focus on these value-added services, typically bringing together a cohort of companies that receive mentoring and other types of assistance for a finite period of time to develop their products, establish their businesses and prepare for first round financing.

In each of these models, the goal of the corporation is to gain a competitive advantage by fostering innovative new businesses to acquire, and preventing them from becoming future competitors. The frenzy among U.S. food companies to launch these investment models is striking: of the 25 top food and beverage companies with a major presence in the U.S. (including foodservice and ingredient companies), 18 have an active corporate venture program. Eight have been formed since 2016.

Beyond Meat, a company that develops plant based protein meat substitutes, is a perfect example of the benefits and tensions that arise in the Big Food / Small Food dance. The company has raised multiple rounds of financing: in 2015 from General Mills’ venture group 301 Inc., and in 2016 and 2017 from Tyson’s venture group Tyson New Ventures. On its website the founder defends his decision to take investment from Tyson, a company with very different views about animals: “The good news is that Tyson and I can—and do—agree on many other things including: the need for sustainable protein for a growing global population; that innovation can fuel growth and profit; and that business best serves the consumer by offering choice.”

Beyond Meat, a company that develops plant based protein meat substitutes, is a perfect example of the benefits and tensions that arise in the Big Food / Small Food dance. The company has raised multiple rounds of financing: in 2015 from General Mills’ venture group 301 Inc., and in 2016 and 2017 from Tyson’s venture group Tyson New Ventures. On its website the founder defends his decision to take investment from Tyson, a company with very different views about animals: “The good news is that Tyson and I can—and do—agree on many other things including: the need for sustainable protein for a growing global population; that innovation can fuel growth and profit; and that business best serves the consumer by offering choice.”

In my recent work in the Good Food industry, I have held the perspective that while there is much to lament about the industrial food system in the U.S., there is also a great deal to be gained by bringing the two worlds together. The benefits of scale in sourcing, production and distribution are essential to a sustainable and prosperous food economy unless we are willing as a society to spend more of our household income on food. And it’s a welcome comeuppance for the Big Food players to see their market shares erode as consumers shout with their wallets about improving the lives and lands that are degraded, sickened and exploited by the traditional food system. I’m eager and optimistic for the net gains we’ll see as this Big Food / Small Food intersection widens and brings more exciting, nutritious, sustainable products to market and increases the accessibility of specialty, niche products to a more economically diverse set of consumers, while bringing more wealth to small business owners and farmers alike.

We’d love to know what you think about this emerging trend with Big Food / Small Food. How do you feel about it? Is this good for consumers? For farmers? For entrepreneurs? Share your thoughts here!

Image: Monkey Business Images/Shutterstock.com

very useful article for our business, especially for food wholesalers. Great points you have there, Thanks for this post.