Last night I had the genuine pleasure of sharing a few remarks about sustainable food systems with a group of food industry professionals in Chicago. It was an event hosted by Chicagoland Food & Beverage Network, formed last year to catalyze the 4,500 food companies in Chicago into an economic engine to drive growth, create jobs and revitalize neighborhoods across the region. Gathered together were people representing Big Food, small food, and everything in between.

They came to network, to enjoy a farm-to-table experience at The Roof Crop™ — a rooftop farm that uses a comprehensive green-roof system developed by Omni Ecosystems — and to learn about how to develop and sustain local and regional food systems.

I was the perfect messenger for that topic, having spent 20 years working in Big Food and the last 10 helping communities across the country build sustainable food systems and businesses. But I felt the challenge: how do I convey the values underpinning the Good Food movement to a crowd that might be as ignorant as I was just a short time ago?

As I began to prepare my remarks, I realized that the journey in my own understanding was precisely what might help this group appreciate the “other side” of the food industry, and that it might help some readers of our blog, too. The complete narrative of the talk is shared below in the way I prepared it, or you can skip to the main points regarding food systems by clicking here.

Dining on the Rooftop: A Farm-to-Table Experience

Welcome to this very special place. I hope you enjoyed your time networking and experiencing this amazing rooftop farm. It is about as hyper-local as you can get; practically a chef’s garden.

Tonight’s presentation is billed:

Eating “local”: it’s more than a buzzword, it’s a new economy. Consumers’ renewed interest in where their food comes from, sustainability, as well as decreasing their carbon footprint, is transforming food production and sales — from farm to table. What does that really mean? How do we innovate and recreate systems and businesses to aggregate, process, market and distribute agricultural products to local customers? Join us for cocktails and dinner and learn from Kathy Nyquist as she explains how to develop and sustain local and regional food systems.

So tonight I plan to talk about food systems, what they are, and why a room full of food industry professionals should care about them. I’ll use a few stories to illustrate the transformation that occurred in me as I left the “Big Food” world and started a business that is the antithesis — a consulting firm, New Venture Advisors, that helps to build local food systems and startup food businesses in the Good Food space.

I sometimes think “Does anyone want to hear this anymore? Isn’t my story a bit tired by now?” But every time I share my story, I find that it inspires someone to step out and do something different, take a chance with their work and career, or think about the work that they are doing in a new and more relevant way. I hope this is the case for you.

I do not expect that many of you believe you have a good understanding of food systems. They are complex! They involve multiple stakeholders — consumers, farmers, workers — and businesses large and small that connect and serve them. And they are tied to so many aspects of human experience:

- Of course life itself

- Our health — something understood since the beginning of civilization. “Let thy food be thy medicine” is attributed to Hippocrates, and an Egyptian pyramid inscription from 3800 B.C. states: “Humans live on one-quarter of what they eat. On the other three-quarters lives their doctor.”

- National security — according to the British security service “Any society is four meals away from anarchy”

- Our identity — regional cuisines and ancestral foods define where we come from and make travel and gathering together over meals so enriching

- And our natural resources — agriculture is the industry with the highest use of our land and water

In all this complexity and struggle is a wonderful alchemy that sustains life and provides the moments of connection that make us human. I would be hard pressed to imagine an industry that provides as much common experience. But I was not prepared for the transformation that would happen in my own understanding of the food industry when I took my first job more than 30 years ago.

I’ve had a long career in food, first in advertising at two big agencies in Chicago — Y&R and Leo Burnett — then at Kraft Foods. I promoted some of the world’s leading brands — Frito Lay, Coca-Cola, Johnny Walker, Kraft Singles, Mac & Cheese — but in over 20 years of working in food, I cannot recall a single conversation in the workplace regarding agriculture. There was one meeting in which we discussed the price of milk futures because herds were being culled in New Zealand, and another in which we were encouraged to support the Farm Bill, a meeting that went completely over my head. Little did I know how closely my work would be impacted by policy just a few years hence.

I had been at Kraft about 10 years when Chef Homaro Cantu visited our campus for an Innovation Day. We often invited chefs to speak with us about trends, recognizing that they see and influence food and flavor trends long before they make their way to the masses and eventually into products made by companies like Kraft. That day Chef Cantu shared that demand for local food was the most profound trend he had ever witnessed in his career, and it showed no signs of abating. I left pondering how Kraft might be able to respond. It seemed antithetical to our business model.

With this volleying in my brain, I became restless. I decided to conduct my own pantry study — an ethnographic research technique we used with consumers to understand how they interacted with our products. Not one thing in my pantry was made by Kraft, but my crisper was jammed with fruits and vegetables. I thought “If I’m going to work in food, I should work on what I myself value.” This was the first thought I had regarding food values, something that would later define so much of my work.

About this time I reconnected with a friend who had returned from working in refugee camps in Central America. He was an electrical engineer by training, and during a short hospital stay, he became obsessed with reading books about hydroponics. He could see how production techniques could provide fresh food in places where supply chains were cut off, land and water were scarce, and the need was dire. This was the first conversation I ever had about food security.

I seized on the intersection of this technology and the local food movement. Why not an indoor farm in Chicago? What could be fresher than food grown right in the city and delivered the same day? I convinced my friend to enter the New Venture Challenge, a business plan competition through an MBA program I was completing at Chicago Booth.

We set about writing our business plan, and rather quickly put it aside when we discovered that it would take 19 years for our brilliant technology to pay back investors. But in the process, I began to network with the chefs and influencers of the local food movement in Chicago, and of course met Jim Slama, founder of FamilyFarmed. Jim had spent 10 years doing political advocacy work in support of sustainable farming and sustaining farmers, and recognized that in order to go any farther in changing food and agriculture in America, the market would have to pick up where policy left off. He could see the role that local food systems played in this marketplace and the need for infrastructure to strengthen it.

We teamed up to start developing businesses that would do just that. At this time my capitalist mind is whetted sharp from Kraft and Booth and I’m thinking, “This local food thing is a juggernaut of opportunity that we are going to ride to riches.” Meanwhile, Jim is saying “Developing markets for local food is the answer to revolutionizing the American diet and giving the farmers who grow food sustainably better livelihoods so they can educate their children.” This is the first time I was confronted by values concerning equity in the food system, and I hoped that my greed didn’t show.

Now you might be thinking, Why does the local food market need to be developed? Haven’t farmers been feeding their neighbors since forever?

The person who taught me the most about the problems small farmers face was an organic distributor in Chicago. He wanted to carry Illinois-grown produce but could not get the supply. Smaller farms that grew food crops were too few and far between for him to efficiently pick up.

He explained how there used to be packing houses dotted all across the U.S. that were like grain elevators — places where many farmers could bring their products to be packed and shipped. As agriculture scaled up, farms expanded and became grower-packer-shippers, performing all of these functions on the farm. Over time this shared infrastructure literally rusted out. This left small farmers with limited means to access the formal wholesale supply chain that moves 99% of the food that we eat.

Today, many small farmers who grow the delicious local food that everyone craves are limited to marketing directly to consumers — like box programs, farmers markets, and farmstands. Personally, I don’t want to buy my groceries that way. Visiting the farmers market by me is a pain. There’s no parking, it’s hot, it’s raining, it’s Saturday morning.

It’s a pain for farmers too. They have to get up at 3AM, drive for hours, stand in the heat and rain, and hope they sell enough to make it all worth it. Some farmers love it, but there are many who would rather just stay home and farm.

And while we love eating on this splendid rooftop, I’d like to see good local food in hospitals, schools, and everyday places we eat. I’d like to buy it at Jewel.

Plus, its expensive to buy through direct channels. Local food that is direct marketed or moves through short supply chains is more expensive, partly because it does not enjoy the awesome efficiency of the long supply chains that move goods through our national and global food system.

It’s not just infrastructure that disconnects farmers from the wholesalers that move the majority of our food. It’s also standards that are hard for some small farmers to meet. Standards we call post harvest handling.

Why do wholesalers have standards? Why can’t they just sell whatever comes from the farm?

A big reason is cost. Large chain restaurants manage inputs down to cost per plate, and that cost is mostly labor and waste. They control those costs through standardization. Big farms have made standardization a core competency. They can grow cukes and tomatoes like widgets with moisture content, shape, size, and count per box all consistent. A line cook can rip open a box knowing exactly what’s inside and work through it in no time. And the distributors bring these boxes in a steady stream from farms north and south across the Americas to supply these widgets year round.

This standardization is very difficult for a small farmer. They have smaller volumes from which to grade out non-standard items, with less experience overall. There are a few wholesalers who get how hard it is for small farmers, and make allowances because their customers are asking for more local products. But when a local farmer’s products make it to a local customer, I call it a small miracle.

I was with this distributor one day when a pallet of produce arrived from a local farm. He had ordered a variety of items: melons, tomatoes, cukes. He opened up a box of cucumbers. He probably knew just from the size of the box something was off. Inside were Japanese cucumbers that had grown like snakes — in a hodgepodge of shapes and sizes. He goodnaturedly threw his hands in the air and said “That’s local.” But what it meant for him was finding a customer who could deal with it. And that adds expense.

Now let’s go up a degree of difficulty. Let’s say a grocery chain wants to promote watermelon from X farm in the weekly flyer, or a chain restaurant wants to menu beef from Y ranch. They want to because this is what their customers want and will pay a premium for. And that would be great for the grocery store, the restaurant, and the farm. The farm might earn more for its melon or beef because it’s no longer a commodity, it’s now a branded product that can command a premium.

Today that distributor has one slot for watermelon and one slot for a cut of beef. For the farm name to be transparent to buyers on a price list, the distributor would have to set up a slot for each farm supplying each item, which could be multiple farms over the course of a season. That may be impossible depending on the capacity of the warehouse.

There are workarounds but these are also expensive. Unfortunately even where this is done, much of the premium does not make it back to the farmer. Maybe this is something blockchain will ultimately make as frictionless as ordering an Uber, but today it stands as one of the main reasons more of the big distributors do not have a great farm-identified, fresh, local program that provides the highest income opportunity for farmers.

Why am I telling you these stories?

To help you understand why finding this great food in everyday places is so rare. And that when you do find it, why it is so expensive. And that when you read headlines like “Farm-To-Table Shouldn’t Only Be For Rich White People” there are practical reasons rich people get most of this delicious food.

And because these reasons explain the recent focus on developing local and regional food systems. And that should matter to each person in this room. Let me explain why.

Food industry professionals understand supply chains. They are some of the most complex networks of relationships of any industry. Which makes sense. It’s an industry that every human being interacts with, multiple times per day, in every location on the planet.

Supply chains are different than food systems. Supply chains relate to a specific product and are the reason you might be enjoying an ice cream on a hot summer day. It’s how the eggs, milk, and sugar came from a farmer to a processing center to the freezer at a local grocery store.

Food systems, on the other hand, are the geographic region in which supply chains operate and encompass every process and type of infrastructure needed to feed people.

They are depicted in different ways as you can see in this Sustainable Food System Models handout — linear like the example on the top page one, or below as a closed loop that recognizes the connection between waste and inputs to production.

For local and regional food systems to function, they need all aspects of these processes and infrastructure to be present. This is important for a number of reasons.

One is food security. If as the British Security Service stated “Any society is four meals away from anarchy,” supply chain disruptions are a homeland security issue. I was in a meeting in which someone hypothesized, “Imagine if the bridges across the Mississippi River were destroyed. Could we feed ourselves in Illinois if we couldn’t import from California and other western states?” The answer is no.

A second reason is carbon footprint. In many areas, food travels long distances for processing only to be shipped back and marketed as “local”. Whether this actually has a higher carbon footprint vs. smaller scale processing operations in local markets can be debated, but it certainly creates a disadvantage for producers. I met with a meat producer in West Virginia who drove most of one full day to have animals processed and then drove back to pick up the cuts. That’s almost four days, four trips, each time she harvested her animals.

This happens in communities all over America where small scale processing has been abandoned as mega processing facilities were built, and state and federal inspection policies made it burdensome for smaller facilities to compete.

A third reason is economic opportunity. Jobs, wages, and profits that stay in local economies can help improve communities, especially in rural and lower income areas. Plus, when the right infrastructure is available locally, it provides the foundation for innovation, whether it’s

- programs that share technical know-how to improve farm and food operations,

- incubators and accelerators like we have here in Chicago, or a tiny kitchen incubator in northern Wisconsin that served 200 entrepreneurs over a decade,

- avenues for farms and food entrepreneurs to reach customers through regional supply chains to start and grow their businesses.

It’s important to have all of these components. But the Good Food movement takes this further. For local and regional food systems to become sustainable, they need much more.

Sustainability has many dimensions — you all know that. There is a financial resiliency piece (profit), a resource conservation piece (planet), and a food access, health equity and worker conditions piece (people).

Most of the work we do at New Venture Advisors is on that first dimension — helping communities and entrepreneurs build businesses that sustain themselves financially, while also working to support a mission tied to the other dimensions. Much of our work is related to infrastructure development — regional aggregators, distributors, food business incubators, commercial kitchens, and processing facilities; and food centers, campuses and districts that bring together multiple of these types of businesses to learn from and trade with each other. We conduct feasibility studies and write business plans for our clients, and help early stage Good Food businesses grow.

Our clients are very diverse — they are entrepreneurs, municipal governments, nonprofits, community development organizations, financial institutions — but despite their diversity there is a cord of continuity that ties them together in the values that underpin their goals. These values are the heartbeat of sustainable food systems. They are what turn a food system into a value chain.

Local Food Value Chains are defined by the relationships between players at each stage, as you can see depicted in the lower graphic on page one of the Sustainable Food System Models handout. Each strives to play their role according to a set of shared values and supports its suppliers and customers in doing the same. A great example is a food hub or distributor that provides support to small farmers to help them scale up. The food hub’s buyers recognize the full value of that service and accepts a higher price as a result.

Not every local or regional food system is that well developed. In many markets buyers are still 100% cost driven, or distributors do nothing to help farmers become successful wholesale suppliers, or farmers are uninterested in producing food crops or converting to organic practices, or shoppers have weak demand for nutritious or locally produced foods.

So in many instances there needs to be a force in these food systems that works without concern for profit, interstitially, to facilitate the development of food system players and encourage values-based transactions between them. This is the force I appreciated least when I started in this work and have come to deeply respect.

What is this force?

It is the nonprofits, NGOs, academic and health care institutions, municipal agencies, food policy councils and thousands of volunteers who work alongside these organizations to run farmers markets, farm to school programs, farmer training, nutrition education, convene stakeholders, make grants, and give their time and financial resources to make their food system something they can be proud of.

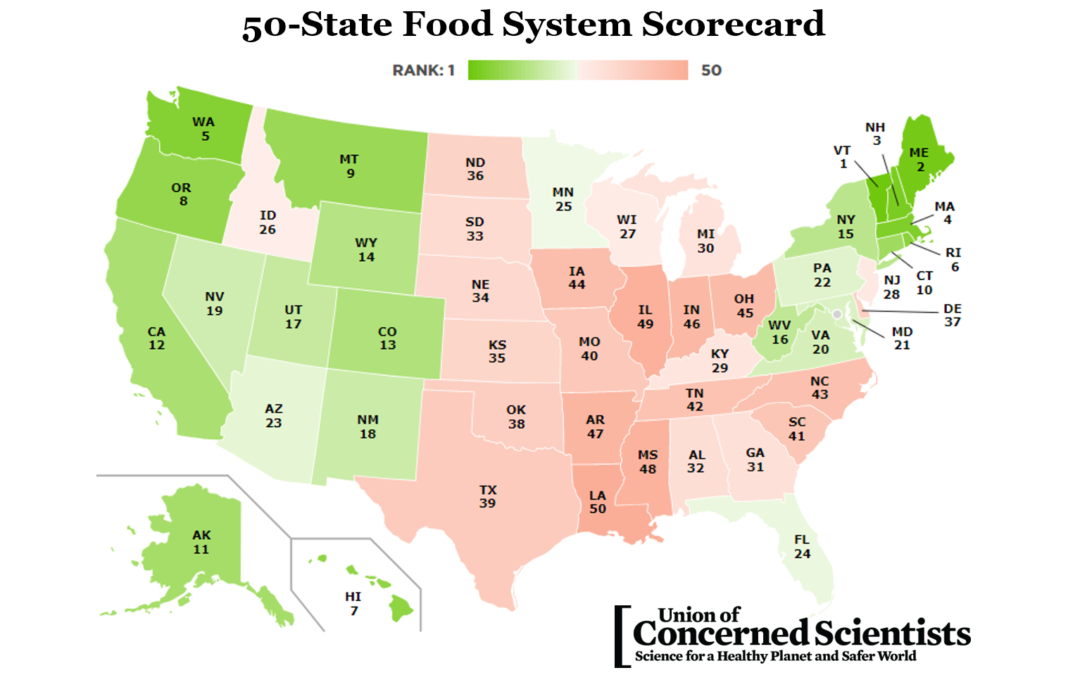

These are the forces that make Vermont the poster state for the Union of Concerned Scientists’ new Food System Scorecard. This is the most comprehensive presentation of the values underpinning sustainable food systems I have ever encountered:

From farm to fork, our food system should be something we are proud of—supporting farmers, workers, and local economies; ensuring that everyone has access to enough nutritious food to stay healthy; and protecting our soil and water for the future.

How close are we to realizing this vision? What do we know about the overall health, sustainability, and equity of the food system across the United States?

UCS created the 50-State Food System Scorecard to help answer these questions. First, we gathered publicly available data on a wide range of indicators. We then grouped the indicators into 10 broad categories and calculated scores for each state in each category. Finally, we averaged state scores across all 10 categories.

Here is a word about UCS from their website:

Our scientists and engineers develop and implement innovative, practical solutions to some of our planet’s most pressing problems—from combating global warming and developing sustainable ways to feed, power, and transport ourselves, to fighting misinformation, advancing racial equity, and reducing the threat of nuclear war. It is supported by individuals, not the government or corporations, which preserves its independence and integrity.

There are limitations with the data, but as a data-minded team we appreciate their attempt, and the comparisons the rankings allow are valuable even without an absolute score. We also LOVE the case studies profiled in each section spotlighting a “force” that is a bright spot amid so much dismal news.

In aggregate, Illinois is #49 out of 50, outperforming only Louisiana. This is embarrassing.

But it is an opportunity for everyone who works in the Chicagoland food industry, or, frankly, anyone who wants to be part of a food system they can be proud of.

Why should you care about food systems?

First, the values at the heart of regional food systems are on every top 10 food trends list: transparent, clean label, local, sustainably produced, socially responsible.

Second, consumers are not evaluating these factors in isolation when making purchase decisions. Foodminds initiated the Food Values Project in 2016 and discovered something profound about the new drivers of food choice. When I was at Kraft it was simple. Three things mattered to consumers: taste, price, convenience. Now food values are rooted in science + emotion. Consumers are considering choices in larger contexts; viewing them in a systems framework. For example, it’s not enough to offer a pro-health benefit — the product must also be sustainable.

In making purchase decisions, consumers consider:

- The entire environment: How was that probiotic produced? Did the dairy farmer use antibiotics? Were the farm workers and animals well treated?

- Their entire diet and lifestyle: Fat is good again. It’s part of balanced nutrition and activity. In fact Organic Valley does not produce low fat cheese because the company believes that fats in the right balance are good for human health.

Another reason you should care is that your actions and stories matter. Here are two worth highlighting.

Kellogg recently introduced Certified Transitional products for the Kashi line. They are buying ingredients from farms that are in the process of transitioning from conventional to organic growing practices. It takes three years for the land to heal. During this transition, farmers can see their incomes drop because as they learn how to farm organically their yields can be lower. Kellogg enters into purchase agreements to help them through this transition period. This helps the farms very tangibly and encourages land stewardship, and it helps Kellogg increase the supply from certified organic acreage over time. The Kashi brand does a beautiful job of telling this story on its packaging. A great example of authentic storytelling.

McDonalds’ exploration of sustainable meat is another example. Say what you will, but if this is done transparently and they make even a small amount of progress toward better practices, it will build capacity that can be leveraged in every region from which McDonald’s sources meat. It could have a massive impact — like Walmart announcing it would reduce solid waste by 30% in three years more than a decade ago. They did it by requiring their suppliers, like Kraft, to reduce packaging waste, and believe it — we did.

So what can you do?

This is a diverse group of food industry professionals. I don’t pretend to know all you are up against. Food is one of those industries that enjoys low barriers to entry but it’s really tough to compete in at scale. Yet here are two things most of us can do to encourage these changes:

1. Recognize that you are part of a food system, not just a supply chain. Be open minded and as generous as you can be with your suppliers and customers who are incurring costs to change the way they do business.

2. Honor the forces that work so invisibly yet so powerfully to make a food system we can all be proud of. Give them your respect, your time, and your money.

Kathy I enjoyed your comments in this presentation. Everything you said is what I was trying to accomplish with the concept of a state-wide food system in Iowa. I agree 100% with your comments regarding the current constraints and barriers to access to local food through Farmers Markets or CSA systems. Incredibly inefficient and costly.

The fact that Il, IA and ID are 49,44 and 46 on the Scorecard is really quite amazing considering the amount of global food production that takes place in these three states. That said it should also suggest the potential that exists in these states if there were collaborative efforts to scale production and distribution of local foods in these states. The amount of land and livestock that may be diverted to a local food system and network would be extremely immaterial compared to the potential revenue, rural economic opportunities and food security issues that could be addressed. Global food production wouldn’t miss a beat. Anyway. Well said

Hi Shane. Yes, your vision for a statewide network of farms and food hubs in Iowa would go a long way in bringing about the benefits you laid out in your white paper–namely, better livelihoods for farmers and rural communities. I still hold out hope for the interest of other visionaries with the resources to move Iowa’s food system toward your vision. Thanks for reading and for this thoughtful comment.